You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Linguistics – Sanskrit – Russian’ category.

Индоевропейские языки: не из Ирана, а из степи

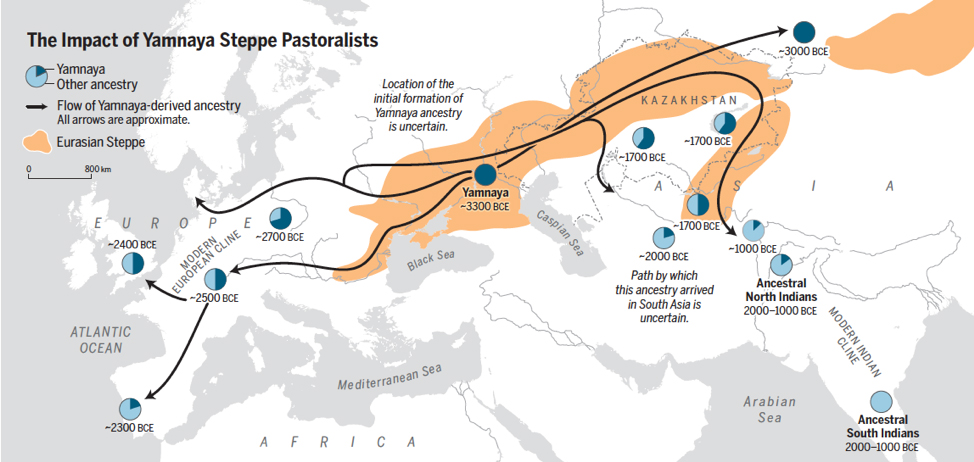

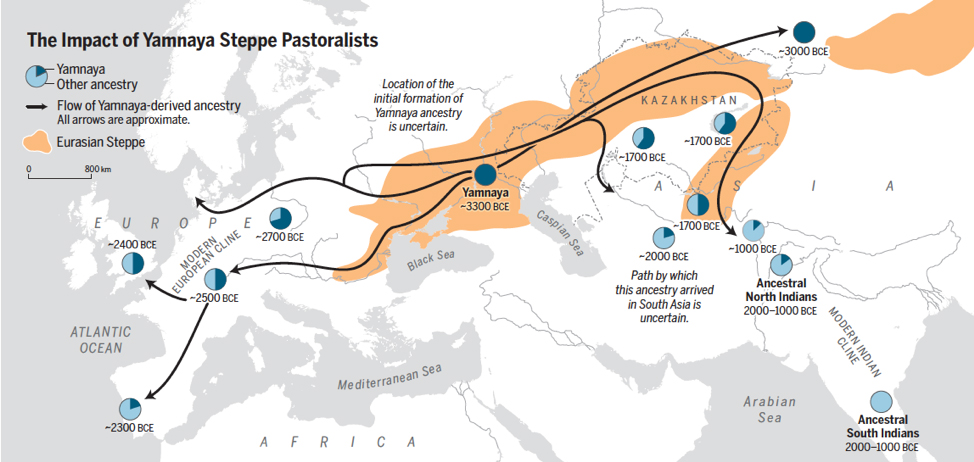

В течение многих лет ученые спорили о происхождении индоевропейских языков в Южной Азии. Некоторые теории указывали на происхождение из района иранского плато, но новые данные свидетельствуют о другом. Исследование под названием «Формирование человеческих популяций в Южной и Центральной Азии» предоставляет отрицательные доказательства против теории иранского плато и вместо этого поддерживает идею о том, что эти языки распространились из степного региона. Я изучал необычайное родство между индоиранскими языками, особенно между ведическим санскритом и славянскими языками. Родство это очевидно, если вы посмотрите на краткий список глаголов и существительных в моих предыдущих блогах. Это лишь малая часть родственных слов, вошедших в готовящийся к изданию Русско-Санскритский Сравнительный словарь. В статье дается некоторое объяснение этой неоспоримой близости.

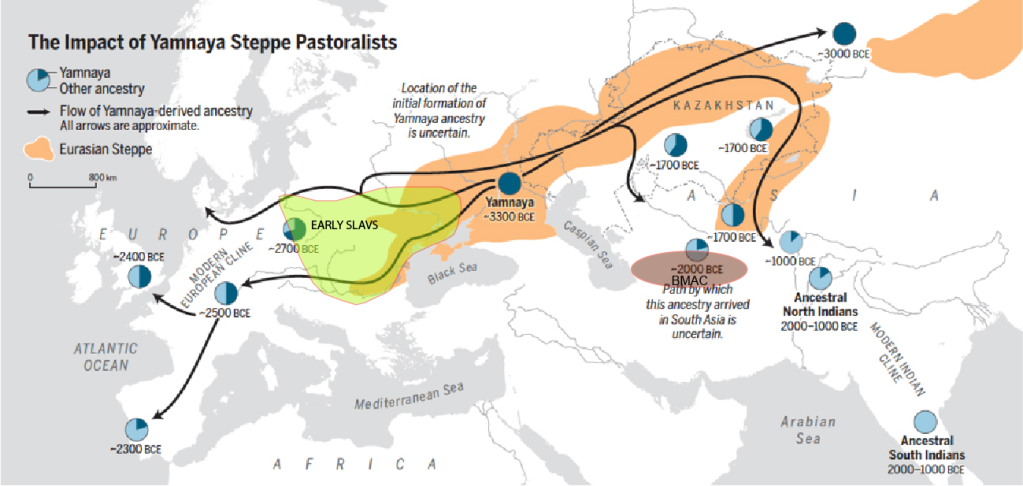

Некоторые исследователи полагают, что Бактрийско-Маргианский археологический комплекс (БМАК) (Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex), древняя цивилизация в Центральной Азии, которая имела место в Центральной Азии, возможно, была источником индоевропейских языков на Индийском субконтиненте, поскольку BMAC находился недалеко от Южной Азии, а между BMAC и людьми цивилизации долины Инда существовали связи. Вопреки предыдущим теориям, новые генетические данные показывают, что основная группа людей региона BMAC не имела какой-либо заметной генетической связи со степными скотоводами и что они не сыграли большой роли в происхождении более поздних жителей Южной Азии. Однако у некоторых людей в регионе BMAC появились гены степных скотоводов примерно в 2000 году до нашей эры, когда они также начали появляться в южном степном регионе.

Крупнейшее в истории исследование древней ДНК освещает тысячелетнюю историю населения Центральной и Южной Азии. (Источник изображения: The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia)

В новом исследовании были изучены данные древних людей из долины Сват в самой северной части Южной Азии, и исследователи обнаружили, что эти степные гены переместились дальше на юг в первой половине 2-го тысячелетия до нашей эры. На их долю приходится до 30% генов современных групп Южной Азии.

Гены степей Южной Азии аналогичны генам Восточной Европы бронзового века. Это говорит о том, что существовала группа людей, которые перемещались между этими регионами, и это движение, возможно, сыграло роль в формировании сходства между индоиранскими и славянскими языками.

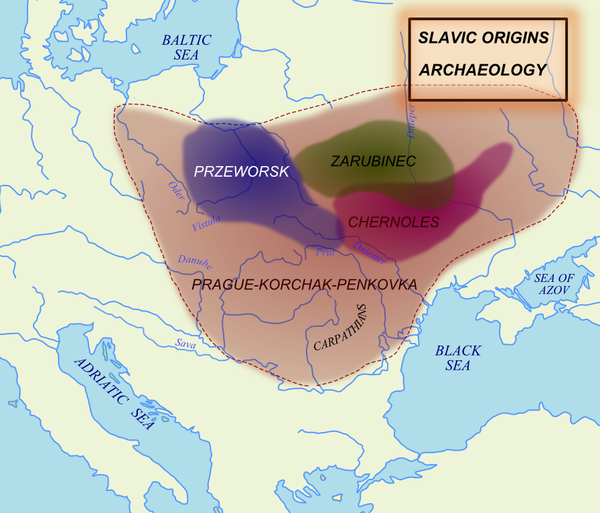

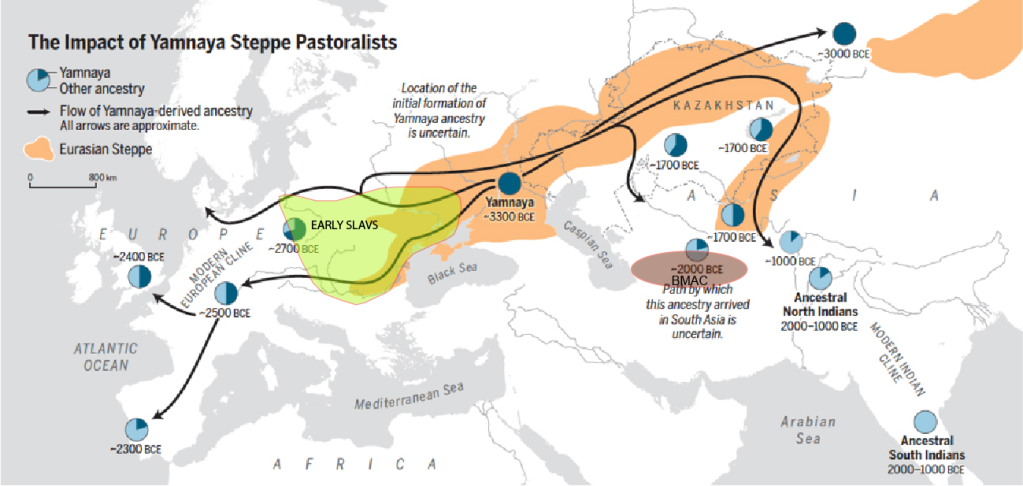

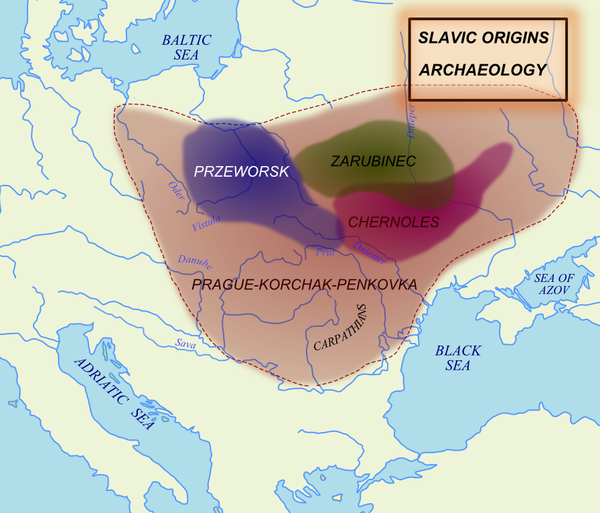

Раннеславянские артефакты чаще всего связаны с зарубинецкой, пшеворской и черняховской культурами, охватывающими западную часть Степи. Примерно в этих же районах предполагается и прародина славян. Праславянский диалект, видимо, обособился и сформировался в Потисье (водосборный бассейн реки Тиса) и Закарпатье.

Это приблизительная адаптация более ранних карт, показывающих расположение ранних славян (зеленый) и BMAC (фиолетовый).

Исследователи проанализировали древнюю ДНК и обнаружили, что их предки из Центральной Степи проникли в Южную Азию в первой половине 2-го тысячелетия до нашей эры. Это генетическое свидетельство может подтвердить связь между степными и индоевропейскими языками Южной Азии.

Материальные культурные различия и генетические связи

Что еще более интригует, так это различия в материальной культуре между Степью и Южной Азией в эпоху бронзы, но несмотря на значительные отличия в артефактах и технологиях, генетические данные свидетельствуют о распространении генов, связанных со Степью, в Южную Азию. Это явление чем-то похоже на ситуацию с культурой «колоколовидных кубков» в Европе, где люди степного происхождения оказали значительное демографическое влияние, но переняли местную материальную культуру.

Однако есть еще одна интересная подсказка: у людей, ответственных за сохранение древних санскритских текстов, таких как брамины, больше генов из степного региона, чем можно было бы ожидать, основываясь на простой смеси различных южноазиатских генов. Это еще одно свидетельство того, что индоевропейские языки в Южной Азии могли прийти из Степного региона до 2000 года до нашей эры.

Indo-European Languages: Not from Iran, But the Steppe

For years, scholars have debated the origins of Indo-European languages in South Asia. Some theories pointed to an Iranian plateau origin, but new evidence suggests a different story. The study titled The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia provides negative evidence against the Iranian plateau theory and instead supports the idea that these languages spread from the Steppe region. I have been studying the extraordinary affinity between Indo-Iranian, especially between Vedic Sanskrit and Slavic languages which is obvious if you look at the short list of verbs and nouns in my earlier blogs. This is just a fraction of the cognate words included in the Russian- Sanskrit Comparative Dictionary being prepared for publication. The article gives some explanation for this undeniable affinity.

Some researchers think that the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) (Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex), an ancient civilization in Central Asia, which was a place in Central Asia, might have been where Indo-European languages began in the Indian subcontinent. They believe this because the BMAC was close to South Asia, and there were connections between the BMAC and the people of the Indus Valley Civilization. Contrary to the previous theories, the new genetic evidence shows that the main group of people of BMAC region didn’t have any notable genetic connection to Steppe pastoralists and that they didn’t play a big part in the ancestry of later South Asians. However, some individuals in the BMAC region started having Steppe pastoralist genes around the year 2000 BCE, which is when it also began appearing in the southern Steppe region.

The largest-ever ancient DNA study illuminates millennia of Central and South Asian population history. (Image source: The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia)

The new study looked at data from ancient people in the Swat Valley in the northernmost part of South Asia, and the researchers found that these Steppe genes moved further south in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. They contributed up to 30% of the genes of modern South Asian groups.

The Steppe genes in South Asia are similar to the ones in Bronze Age Eastern Europe. This suggests that there was a group of people who moved between these regions, and this movement may have played a role in shaping the similarities between Indo-Iranian and Slavic languages.

Early Slavic artefacts are most often linked to the Zarubintsy, Przeworsk and Chernyakhov cultures embrace the Western part of the Steppe.

This is a rough adaptation of the earlier maps showing the locations of Early Slaves (green) and BMAC (purple).

The researchers analysed ancient DNA and found that Central Steppe ancestry made its way into South Asia during the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. This genetic evidence strengthens the connection between the Steppe and Indo-European languages in South Asia. It’s a bit like fitting pieces of a puzzle together, as genetic data supports the idea of language migration from one region to another.

Material Culture Differences and Genetic Links

What’s even more intriguing is the disparity in material culture between the Steppe and South Asia during the Bronze Age. Despite significant differences in artefacts and technologies, genetic evidence suggests the spread of Steppe-related genes into South Asia. This phenomenon is somewhat akin to the Beaker Complex in Europe, where people with Steppe ancestry made significant demographic impacts while adopting local material culture.

However, there’s another interesting clue: the people who have been responsible for preserving ancient Sanskrit texts, like Brahmins, have more genes from the Steppe region than what we would expect based on a simple mix of different South Asian genes. This is another piece of evidence that suggests that the Indo-European languages in South Asia might have come from the Steppe region before the year 2000 BCE.

Просматривая Интернет, обратил внимание на несколько тем, обсуждающих «Ведическую астрономию» и утверждающих, что «Ригведа описывает орбиту Солнца и притяжение планет». В поддержку этого утверждения обычно цитируются несколько строф Ригведы (10.22.14, 10.149.1, 1.164.13, 1.35.9). Хочу продемонстрировать, что «перевод» гимна Ригведы 1.35.9, который повторяется и публикуется на различных сайтах и в блогах:

«Солнце движется по своей орбите, но удерживает Землю и другие небесные тела таким образом, чтобы они не сталкивались друг с другом силой притяжения».

является ложным и вводящим в заблуждение.

Я только что закончил изучение этого гимна и могу прочитать большую его часть наизусть, поэтому и был ошеломлён этим «переводом», который не имеет ничего общего с оригинальным ведическим текстом. Если у вас есть желание, терпение и немного свободного времени, хочу продемонстрировать, почему это фальсификация и обман.

Строфа 1.35.9 важна, поскольку она является неотъемлемой частью церемонии упанаяны (для вайшьи). Точный текст этой строфы (с ударениями) следующий:

हिर॑ण्यपाणिः सवि॒ता विच॑र्षणिरु॒भे द्यावा॑पृथि॒वी अ॒न्तरी॑यते

अपामी॑वां॒ बाध॑ते॒ वेति॒ सूर्य॑म॒भि कृ॒ष्णेन॒ रज॑सा॒ द्यामृ॑णोति

в транслитерации IAST:

híraṇyapāṇiḥ savitā́ vícarṣaṇir ubhé dyā́vāpr̥thivī́ antár īyate

ápā́mīvām bā́dhate véti sū́ryam abhí kr̥ṣṇéna rájasā dyā́m r̥ṇoti

Транслитерация падапатхи (с без сандхи и ударений):

hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ǀ savitā ǀ vi-carṣaṇiḥ ǀ ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ ǀ īyate ǀ

apa ǀ amīvām ǀ bādhate ǀ veti ǀ sūryam ǀ abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām ǀ ṛṇoti ǁ

Теперь мы подходим к самой важной части перевода этих двух строк. Некоторые из индийских читателей могут воскликнуть в этот момент: «Никогда не читайте переводы Вед западных ученых! Они делают ошибки, потому что на санскрите одно слово имеет несколько значений». Поэтому я и приглашаю вас присоединиться к увлекательному путешествию и шаг за шагом идти со мной по ходу перевода.

Прежде всего, нам необходимо разделить два процесса «перевод» и «интерпретация».

Цель переводчика — точно передать суть исходного текста, гарантируя, что переведенная версия сохранит ту же грамматическую структуру и буквальное значение, что и оригинал. Он включает в себя тщательный процесс понимания грамматики, синтаксиса и нюансов как исходного, так и целевого языка. В нашем случае эта задача может быть весьма сложной, поскольку мы имеем дело с древними текстами, такими как Ригведа, которые изначально были созданы на языке, известном как «Ведический», отделённом от нашего времени как минимум на 3500 лет.

Интерпретация предполагает анализ и объяснение смысла текста. В то время как перевод фокусируется на передаче буквального значения, интерпретация направлена на раскрытие основных сообщений, символизма и культурного значения в данном произведении.

Теперь обратимся к нашему переводу 1.35.9.

Поскольку русский язык во многом сохраняет древнюю индоевропейскую и ведическую грамматику (имеющую схожие закономерности (склонения и спряжения ), анализировать текст будем, используя метод задавания условных вопросов, применяемый при преподавании русской грамматики в школе.

Первым важным шагом является определение действующего лица или субъекта предложения. В некоторых строфах это не всегда легко, но, к счастью, в нашем случае все просто. Задаем вопрос КТО? Очевидный ответ – savitā. По окончанию – ā мы заключаем, что это именительный падеж единственного числа мужского рода от именной основы savitṛ. Окончание tṛ- говорит нам, что это существительное-агент или «исполнитель/деятель». Отнимая это окончание, мы получаем основу savi – и далее, удаляя связующую гласную, мы приходим к основе sau- / sav-. Применяя в обратном порядке фонетическое правило вриддхи, мы приходим к элементарному глагольному корню sū–. Это один из фундаментальных ведических корней, означающий «приводить в движение, побуждать, побуждать, оживлять, создавать, производить». Из этого корня образуются такие важные слова, как sūrya «Солнце», sūnu м. ‘сын, ребенок, потомство’ и многие другие.

Объединив все это вместе как savitṛ, мы уверенно устанавливаем значение как «тот, кто приводит в движение, побуждает, побуждает, оживляет, творит, производит». Это хорошо согласуется с характером Солнца или солнечного божества.

Следующий вопрос: КАКОЙ savitā?

Есть два прилагательных, согласующихся с savitā в именительном падеже единственного числа, мужского рода (окончание падежа – ḥ ), описывающих его качества: hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ и vi-carṣaṇiḥ.

Первый представляет собой сложное слово с первым компонентом hiraṇya – «золото; золотой, сделанный из золота» и второй — pani – «рука» (первоначально *palni, относящееся к греч. παλάμη ; лат. palma ; англ.сак. folm ). Таким образом, это сложное слово уверенно переводится как «златоторукий».

Следующее слово vi-carṣaṇiḥ несколько сложнее. Отнимая падежное окончание, мы получаем основу vi-carṣaṇi– , удаляя приставку vi- , получаем прилагательное karṣaṇi – происходящее от глагольного корня kṛṣ- с центральным значением ‘тащить, тянуть; делать борозды, пахать» (начальная буква «с» — палатализованная «k» ). Следуя древнеиндийскому грамматику Яске, это слово следует перевести как «пахать, возделывать», что в более широком смысле означает «занятый чем-то, активный». Примечательно, что это слово звучит созвучно глаголу vi-car, кардинальное значение которого «двигаться быстро, бродить, бродить вокруг или сквозь, пересекать», создавая дополнительное ощущение быстрого движения. Намек на пахоту и занятость может дать подсказку, почему эта строфа была специально выбрана для Вайшьи в церемонии упанаяны. Более того, в Ведах есть существительное во множественном числе carṣaṇi «земледельцы (в отличие от кочевников)», народ, люди, раса», означающее пять народов (páñca carṣaṇī́ḥ «пять народов» в RV 5.86.2). Есть еще одно возможное объяснение. Ригведа передавалась устно на протяжении многих поколений, прежде чем была записана. Хотя священники старались передавать гимны как можно точнее, мы не можем исключить возможности неправильного произношения или ошибки. Существует глагол cakṣ — «видеть, наблюдать» и его префиксная форма vi–cakṣ — «видеть отчетливо, рассматривать». Возможно, нам следует понимать это проблематичное слово как vi–cakṣaṇiḥ, что может означать «взирающий, смотрящий». Это согласуется с характером Савитра – «надзирающего за всеми живыми существами».

Теперь мы можем перевести деятеля/субъекта hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ـ savitā ـ vi-carshaṇiḥ как «златоторукий, активно действующий Савитр». Также имея в виду сложную (и, вероятно, преднамеренную) ассоциацию vi-carṣaṇī́ḥ с быстротой, а также с «земледельцами» (в отличие от кочевников)’, мужчины, народ, раса’.

Далее следует вопрос ЧТО ОН ДЕЛАЕТ? Чтобы ответить на него, нам нужно найти все глаголы в строфе. Мы легко идентифицируем четыре глагола: īyate, bā́dhate, véti and ṛṇoti. Все они настоящего времени, 3 лица, единственного числа (он/она/оно), окончания -te/-ti , поэтому мы уверены, что все они относятся к savitā. Давайте рассмотрим их каждый отдельно.

(1) īyate — это интенсивная форма глагола i- «идти быстро или неоднократно, приходить, бродить, бежать, распространяться, передвигаться», что соответствует характеру Савитра/Солнца.

(2) bā́dhate — это форма корня bādh, который в ведическом значении означает «давить, заставлять, отгонять, отталкивать, удалять».

(3) véti – это форма корня vī – «приводить в движение, возбуждать, возбуждать, побуждать»; идти, приближаться».

(4) ṛṇoti – это форма корня ṛ- ‘идти, двигаться, подниматься, стремиться вверх; идти навстречу, встретиться, упасть или попасть, достичь, получить».

Объединяя ответы на вопросы КТО? и ЧТО ДЕЛАЕТ? формируем опорную структуру нашего перевода:

златорукий, активно действующий (или взирающий?) Савитр (1) идет быстро, шествует (куда-то), (2) отгоняет/отталкивает (что-то), (3) приводит в движение, возбуждает, побуждает (что-то), (4) поднимается, идёт (на или по направлению к чему-то или куда-то).

Нам нужно только заполнить недостающие части, задавая вторичные вопросы.

- КУДА ИДЕТ? ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ, где ubhe— двойственная форма винительного падежа от ubha «оба» (ср. русские оба, обе); dyāvāpṛthivī – это соединение «дванда», состоящее из слов dyāvā «небо» + pṛthivī «земля или широкий мир» (соответственно также винительный падеж двойного числа); последнее слово antaḥ/antar означает «между» (руск. нутро). Ответ: «идёт/перемещатся между небом и землей».

- ЧТО ОТГОНЯЕТ? apa ǀ amīvām, где apa означает «прочь, прочь», а amīvām — форма винительного падежа множественного числа от amīva — «страдание, ужас, испуг»; мучительный дух, демон; горе, болезнь». Ответ: «отгоняет/отталкивает беды/болезни».

- ЧТО ПРИВОДИТ В ДВИЖЕНИЕ, ЧТО ПРОБУЖДАЕТ? sūryam— винительный падеж от sūrya «Сурья/Солнце». Ответ: «приводит в движение/пробуждает Сурью/Солнце».

- ПОДНИМАЕТСЯ/ИДЕТ КУДА? abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām, где abhi означает ‘внутри, поверх, на; к, к, в направлении, против, мимо’; kṛṣṇena — это инструментальный падеж (здесь выражающий местный падеж (подобдно русск. иду дорогой длинною) слова kṛṣṇa «тёмный, чёрный», rajasā — это инструментальный падеж (выражающий местный падеж) rajas «область (промежуточная сфера пара или тумана, область облаков между мирами небес и землёй)» и dyām — винительный падеж от div, dyu «небо». Слова kṛṣṇena rajasā образуют единое целое, означающее «темная + (промежуточная) область». Ответ: «по на темнной (промежуточной) области неба» или, грамматически точнее, творительным (инструментальным) падежом, как в строфе: «темной (промежуточной) областью» неба.

Теперь мы можем собрать все элементы и получить полный перевод (все еще нуждающийся в доработке):

Златорукий, активно действующий Савитр ходит/перемещается быстро/многократно между небом и землей, (он) отгоняет/отражает беды/болезни, (он) вызывает/пробуждает Сурью/Солнце, (он) достигает/поднимается/идет к небесам тёмной промежуточной областью.

Давайте теперь сравним наш необработанный перевод с переводом Шри Ауробиндо.

Златорукий всевидящий Савитри перемещается между Небом и Землей ;{он} отгоняет горе, несёт Солнце , идёт темным межмирьем к Небесам .

Как видите, оба текста схожи по смыслу. Слова Шри Ауробиндо более кратки, но ключевые слова содержат ссылки на словарь, дающий дополнительные детали, отражающие его видение и интерпретацию Вед. Главное отличие в интерпретации неясного слова vi-carṣaṇiḥ.

По мнению Майрхофера, «существование прилагательного carṣaṇiḥ «подвижный, активный, активный» […] совершенно сомнительно», он принимает только значение «народ, раса, племя». Есть очень похожее по звучанию прилагательное vicakshaṇa ‘заметный, видимый, яркий, сияющий, великолепный; прозорливый (букв. и рис.), проницательный, умный, мудрый’ от глагола vi-cakṣ ‘отчетливо видеть, разглядывать, рассматривать, воспринимать, рассматривать’. Форма наст. времени, 3 лица, ед. числа vi-caṣṭe ‘(он) отчетливо видит, рассматривает, озирает’, воспринимает’, так что, видимо, в переводе Шри Ауробиндо это слово понималось именно в этом смысле, поскольку Савитр в другой строфе описывается как наблюдающий за всеми существами ( RV 1.35.2 «ā́ devó yāti bhúvanāni páśyan» ‘едет бог Савитр озирая живые существа’). Мы не можем точно перевести это слово, и его нужно как-то интерпретировать. Так, например, в русском переводе Елизаренковой это место трактуется «Златорукий Савитар, повелитель людского рода». В немецком переводе Гельднера это слово переведено как «der Ausgezeichnete» ‘великолепный, прекрасный’.

Здесь мы подходим к решающему моменту интерпретации. Значение этой строфы можно интерпретировать по-разному. Если вы практикуете традиционный индуизм, вы будете интерпретировать Савитра как одно из божеств ведического пантеона и одного из Адитьев, то есть потомка ведического божества Адити. Если вы разделяете идеи Даянанда Сарасвати, вы будете рассматривать Савитр как другое слово, обозначающее «солнце», и как одно из проявлений Верховного Господа. В любом случае ваше понимание/интерпретация может отличаться, но это не означает, что вы можете свободно изменять грамматику, синтаксис и другие фундаментальные элементы буквального перевода. Поэтому космический «перевод», с которого мы начали наше обсуждение, совершенно ложен и вводит в заблуждение.

Надеюсь, вам понравилось путешествие в удивительный мир Ригведы. Пожалуйста, не стесняйтесь комментировать или задавать вопросы.

[H1] слияние звуков через границы слов и смена звуков при взаимодействии с соседними звуками или из-за грамматической функции соседних слов.

Browsing the Internet, I came across multiple threads discussing “Vedic Astronomy,” claiming that “Rig Veda describes Sun Orbit and attraction of planets.” Several stanzas of Rig Veda (10.22.14, 10.149.1, 1.164.13, 1.35.9) are usually quoted to support this claim. I would like to demonstrate that the “translation” of the Rig Veda hymn 1.35.9 which is repeated and re-posted across various sites and blogs:

“The sun moves in its own orbit but holding earth and other heavenly bodies in a manner that they do not collide with each other through force of attraction.”

is false and misleading.

I have just finished studying this hymn and can recite most of it by heart so I was stunned by this “translation” which has nothing to do with the original Vedic text. If you have the desire, patience and a bit of spare time I intend to demonstrate why it is a falsification and a hoax.

The stanza 1.35.9 is important because it is an essential part of the upanayana ceremony (for Vaishya). The exact text of this stanza (with accents) is as follows:

हिर॑ण्यपाणिः सवि॒ता विच॑र्षणिरु॒भे द्यावा॑पृथि॒वी अ॒न्तरी॑यते

अपामी॑वां॒ बाध॑ते॒ वेति॒ सूर्य॑म॒भि कृ॒ष्णेन॒ रज॑सा॒ द्यामृ॑णोति

in the IAST transliteration:

híraṇyapāṇiḥ savitā́ vícarṣaṇir ubhé dyā́vāpr̥thivī́ antár īyate

ápā́mīvām bā́dhate véti sū́ryam abhí kr̥ṣṇéna rájasā dyā́m r̥ṇoti

Padapatha (with joining sandhi [H1] and accents removed) transliteration is:

hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ǀ savitā ǀ vi-carṣaṇiḥ ǀ ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ ǀ īyate ǀ

apa ǀ amīvām ǀ bādhate ǀ veti ǀ sūryam ǀ abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām ǀ ṛṇoti ǁ

Now we come to the most important part of translating these two lines. Some of Indian readers may exclaim at this point “Never read translations of Vedas by Western scholars! They make mistakes because in Sanskrit a single word has multiple meaning” so I invite you to join the quest and follow the translation procedure step by step.

First of all, we need to separate the two processes “translation” and “interpretation”.

The translator’s goal is to faithfully capture the essence of the original text, ensuring that the translated version maintains the same grammatical structure and literal meaning as the source. It involves a meticulous process of understanding the grammar, syntax, and nuances of both the source language and the target language. In our case this task can be quite challenging because we are dealing with ancient texts like the Rig Veda, which was originally composed in a language known as “Vedic,” separated from our times by at least 3500 years.

Interpretation involves the analysis and explanation of the meaning behind the text. While translation focuses on conveying the literal meaning, interpretation aims to uncover the underlying messages, symbolism, and cultural significance within a given piece of work.

Now to our translation of 1.35.9.

Since Russian in many ways preserves the ancient Indo-European and Vedic grammar (having similar declension and conjugation patterns), we shall analyse the text using the method of questioning used in teaching Russian grammar at school.

The first important step is to determine the Actor or the Subject of the sentence. It is not always easy in some stanzas but, fortunately, in our case it is straightforward. We ask the question WHO? The obvious answer is savitā. By its ending –ā we deduce that this is Nominative case, singular, masculine from the nominal base savitṛ-. The base ending tṛ- tells us that it is an agent noun or ‘performer/doer’ . Taking this ending off we get the base savi– and further taking off the linking vowel we arrive to the bare root sau-/sav-. By applying backwards the vṛddhi phonetic rule we come to the elementary verbal root sū-. It is one of the most fundamental Vedic roots meaning ‘to set in motion, urge, impel, vivify, create, produce’. This root makes such important words as sūrya ‘the Sun’, sūnu m. ‘a son, child, offspring’ and many others.

Putting it all together as savitṛ- we confidently establish the meaning as ‘one who sets in motion, urges, impels, vivifies, creates, produces’. This agrees well with the character of the Sun or a solar deity.

The next question is WHAT savitā? There are two adjectives coordinated with savitā in Nominative case, singular, masculine (case ending –ḥ) describing his qualities: hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ and vi-carṣaṇiḥ.

The first one is a compound with the first component hiraṇya– ‘gold; golden, made of gold’ and the second is pāṇi– ‘hand’ (originally *palni related to Gk. παλάμη; Lat. palma; Angl.Sax. folm). The compound is thus confidently translated as ‘golden-handed’.

The next word vi-carṣaṇiḥ is somewhat more challenging. Taking off the case ending we get the base ví-carṣaṇi-, removing the prefix vi- we obtain the adjective carṣaṇi– deriving from the verbal root kṛṣ- with the central meaning ‘to drag, pull; make furrows, plough’ (the initial c is a palatalised k). Following the ancient Indian grammarian Yāska this word is to be translated as ‘ploughing, cultivating’ meaning more broadly ‘busy doing something, active’. Notably, this word sounds in tune with the verb vi-car- with the cardinal meaning ‘move swiftly, rove , ramble about or through, traverse’ giving an additional feeling of swift motion. The allusion to ploughing and being busy may give a clue why this stanza was specifically chosen for Vaishya in upanayana ceremony. Furthermore, in Vedic there is a plural noun carṣaṇi ‘cultivators (opposed to nomads)’, men, people, race’ meaning the five peoples (páñca carṣaṇī́ḥ ‘five peoples’ in RV 5.86.2). There is yet another possible explanation. Rig Veda has been passed orally for many generations before it was written down. Although the priests did their best to transfer it on as precisely as possible we cannot exclude chances of mispronunciation or mistake. There is a verb cakṣ– ‘to see, to observe’ and its prefixed form vicakṣ– ‘to see distinctly, view’. Perhaps we should read this problematic word as vi-cakṣaṇiḥ meaning ‘seeing, observing’. This agrees with the character of Savitṛ- as ‘overseeing all living creatures’.

We can now translate the Actor/Subject hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ǀ savitā ǀ vi-carṣaṇiḥ as ‘golden-handed, busily acting Savitr’ also keeping in mind the intricate (and probably intentional) association of vi-carṣaṇiḥ with swiftness and also with ‘cultivators (opposed to nomads)’, men, people, race’.

Next comes the question WHAT DOES HE DO? To answer it we need to look for all verbs in the stanza. We easily identify four verbs īyate, bā́dhate, véti and ṛṇoti. They all have Present Tense, 3 person, singular (he/she/it) endings -te/-ti so we are sure that they all relate to savitā. Let us go though them one by one.

(1) īyate is the intensive form of the verb i- ‘to go quickly or repeatedly, to come, wander, run, spread, get about ‘. This matches the character of Savitr/Sun.

(2) bādhate is a form of the root bādh– with the Vedic meaning ‘to press, force, drive away, repel, remove’.

(3) veti is a form of the root vī– ‘to set in motion, arouse, excite, impel; to go, approach’.

(4) ṛṇoti is a form of the root ṛ- ‘to go, move, rise, tend upwards; to go towards, meet with, fall upon or into, reach, obtain’.

Combining the answers to the questions WHO? and DOING WHAT? we form the back-bone structure of our translation:

golden-handed, busily acting (or overseeing?) Savitr (1) goes quickly, traverses (somewhere), (2) drives away/repels (something), (3) sets in motion, arouses, impels (something), (4) rises, goes (upon or towards something or somewhere).

We only need to fill in the missing bits by asking secondary questions.

- GOES WHERE? ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ where ubhe is an Accusative dual form of ubha both (compare Russian oba, obe ‘both’); dyāvāpṛthivī is a “dvanda” compound made of words dyāvā ‘heaven’ + pṛthivī ‘the earth or wide world’ also Accusative dual; final word antaḥ/antar means ‘between’. The answer is ‘going/traversing between both heaven and earth’.

- REPELLS WHAT? apa ǀ amīvām where apa is ‘away, off’ and amīvām is an Accusative plural form of amīva- ‘distress, terror, fright; tormenting spirit, demon; affliction, disease’. The answer is ‘drives away/repels distresses/diseases’.

- SETS IN MOTION, AROUSES WHAT? sūryam Accusative of sūrya ‘Surya/Sun’. The answer is ‘sets in motion/arouses Surya/Sun’.

- REACHES WHAT? or RISES/ GOES WHERE? abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām where abhi is ‘into, over, upon; to, towards, in the direction of, against, by’; kṛṣṇena is the Instrumental (here expressing Locative) of kṛṣṇa ‘dark, black’, rajasā is Instrumental (expressing Locative) of rajas ‘region (the intermediate sphere of vapour or mist, region of clouds)’ and the Accusative dyām of div, dyu ‘heaven, the sky’. The words kṛṣṇena rajasā are treated grammatically as a pair but they form a single entity meaning ‘dark + (intermediate) region’ so we translate it as a singular. The answer is ‘into/over/upon the dark (intermediate) region of the sky’.

Now we can assemble all the elements and get the whole translation (still in need of polishing):

Golden-handed, busily acting (or overseeing?) Savitr goes/traverses quickly/repeatedly between both heaven and earth, (he) wards off/repels distresses/diseases, (he) incites/arouses Surya/Sun, (he) reaches/rises/goes towards the sky/heaven over/upon/towards the dark-intermediate-region.

Lets us now compare our raw translation with that of Sri Aurobindo

The golden-handed all-seeing Savitri is moved between both Heaven and Earth ; {he} drives away grief, carries the Sun , goes by the dark Mid-world to Heaven .

As you can see both texts are similar in sense. The one by Sri Aurobindo is more concise but the key-words have references to the dictionary providing additional details which reflect his vision and interpretative of the Vedas. The obvious difference, however, is the translation of the obscure word vi-carṣaṇiḥ. According to Mayrhofer “The existence of an adjective carṣaṇiḥ “mobile, active, active” [….] is entirely doubtful” he only accepts the meaning ‘people, race. tribe’. There is a very similarly sounding adjective vicakṣaṇa ‘conspicuous, visible, bright, radiant, splendid; clear-sighted (lit. and fig.), sagacious, clever, wise’ from the verb vi-cakṣ ‘to see distinctly, view, look at, perceive, regard’. Its present tense, 3 person sing. form is vi-caṣṭe ‘(he) sees distinctly, views, looks at’ so, apparently, in the Sri Aurobindo’s translation this word was understood in this sense because Savitr in other stanza is described as overseeing all creatures (RV 1.35.2 “ā́ devó yāti bhúvanāni páśyan” ‘drives god Savitr overseeing living creatures’). There is no way we can translate this word exactly and it has to be interpreted in some way. So, for example, in the Russian translation by Elizarenkova this passage is interpreted as “Golden-armed Savitar, ruler of the human race.” In Geldner’s German translation this word is translated as “der Ausgezeichnete” ‘magnificent, beautiful’.

Here we come to the crucial point of interpretation. One can interpret this stanza meaning in many ways. If you practice the traditional Hinduism, you will interpret Savitr as one of the deities of the Vedic pantheon, and one of the Adityas, i.e., offspring of the Vedic deity Aditi. If you share the ideas of Dayanand Saraswati you will view Savitr as another word for “sun” and as one of the manifestations of The Supreme Lord. In either case, your understanding/interpretation may be different, but this does not mean that you may freely alter the grammar, syntax, and other fundamental elements of the literal translation. Therefore, the cosmic “translation” from which we started our discussion is totally false and misleading.

I hope that you enjoyed the voyage to the awesome world of Rig Veda. Please feel free to comment or ask questions.

[H1]fusion of sounds across word boundaries and the change of sounds due to neighbouring sounds or due to the grammatical function of adjacent words.

I have not published any new posts for several years but the work on the comparative dictionary was continuing. Regrettably, my co-author and teacher Alexander Shaposhikov died last year. However, he has finished most of his part of work and also left many comments that allow me to continue with this project and lead it to the end. Currently, the dictionary is 90 per cent complete. It contains approximately 870 completed entries out of a total of 1000 planned. I hope to publish the dictionary by September 2023.

The dictionary is the first comprehensive study of lexical similarities between Russian and Sanskrit. In creating it, the authors drew on the contributions and historical works of Russian and other linguistic researchers of etymology, especially the Russian Academician O. N. Trubachev and “Etymological Dictionary of Slavic Languages” published by Vinogradov Instutute of Russian Language. This is a demonstration draft with only a small number (90) of entries including words starting with (russian) B (rating 5-3). Progress since the previous draft:

The introductory part has been thoroughly edited and page typesetting largely completed (hyphenation, “hanging” prepositions, spacing etc.).

Dictionary entries have been edited, style and spelling corrected. Proper typesetting of dictionary entries is still to be done. Biblio references were checked, sorted and standardised to GOST. Cover draft was slightly edited.

Please note that in the online text the Devanagari ligatures are not always reproduced correctly and some words seem stuck together, so we recommend to download a .pdf file which is fairly small in size.

________________________

Cловарь является первым систематическим сводом лексических схождений русского и санскрита. При его создании авторы опирались на достижения исторического языкознания, работы по этимологии российских и зарубежных исследователей и особенно на наследие академика О. Н. Трубачёва и «Этимологический словарь славянских языков. Это демонстрационный черновик с небольшим количеством (90) слов, начинающихся с (рус.) B (рейтинг 5-3).

Прогресс по сравнению с предыдущим черновиком:

Вступительная часть тщательно отредактирована, в основном завершена верстка страниц (расстановка переносов, «висячие» предлоги, интервалы и т. д.).

Словарные статьи отредактированы, исправлены стиль и орфография. Надлежащая верстка словарных статей еще предстоит. Библиографические ссылки были проверены, отсортированы и приведены в соответствие с ГОСТ. Проект обложки был немного отредактирован.

Обратите внимание, что в онлайн-тексте лигатуры деванагари не всегда воспроизводятся правильно, а некоторые слова кажутся слипшимися, поэтому мы рекомендуем вам скачать файл .pdf, который имеет довольно небольшой размер.

Мы приветствуем любую конструктивную критику и комментарии.

The new draft of the Russian-Sankrit dictionary is now available at Academia.edu and ResearchGate.

I am sorry to dissapoint some of my readers but we are currently doing only the Russian version. The main differences from the previous draft:

- A draft introduction has been added.

- An outline draft dictionary organisation chaper has been added.

- The dictionary now includes all rating 5 words (242 entries), however entries with lower rating have beed removed from this dtaft.

- Spelling and style mistakes have been corrected.

Your comments and observations are always welcome!

My latest piece of research has finally been published in the on-line version of Filologija journal. The paper analyses in detail a little-known article by Antun Mihanović  highlighting his role as one of the pioneers of Slavonic comparative studies. Although the article was written under the influence of the German romantic nationalism, the ideological pointedness should not overshadow its significance as a remarkable, for the time, piece of comparative linguistic research.

highlighting his role as one of the pioneers of Slavonic comparative studies. Although the article was written under the influence of the German romantic nationalism, the ideological pointedness should not overshadow its significance as a remarkable, for the time, piece of comparative linguistic research.

You can access the paper at the journal’s site.

I hope that many of my followers would find it interesting. Your questions or comments are welcome!

On October 25, 2015 the draft of the Russian-Sanskrit Dictionary of Common and Cognate Words was for the first time presented to the public at the Commemorative meeting dedicated to the 85th anniversary of Academician O. N. Trubačёv organized by the Public International Fund of Slavonic Literature and Culture and Institute of Russian Language by the Russian Academy of Sciences.

On October 25, 2015 the draft of the Russian-Sanskrit Dictionary of Common and Cognate Words was for the first time presented to the public at the Commemorative meeting dedicated to the 85th anniversary of Academician O. N. Trubačёv organized by the Public International Fund of Slavonic Literature and Culture and Institute of Russian Language by the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In a 20 minute report I briefly told about the background of creation of the dictionary and the principal technical aspects of the project.

First lists of similar in sound and meaning Sanskrit and Russian words appeared soon after the discovery of Sanskrit by European philologists but it so happened that the main focus of research in Russia was directed towards comparative analysis within Slavonic languages. This may explain the lack of works directly comparing Slavonic languages with Sanskrit.

Of course, this does not mean that Sanskrit evidence has not been engaged at all in Russian etymological studies. All major Russian etymological dictionaries do contain links to Sanskrit, but often they are more a by-product of the Western Indo-European linguistics than the result of a purposeful and large-scale comparison of Indo-Aryan and Slavic lexicons.

In my speech I particularly stressed that the current situation in which the only comparative Sanskrit-Russian dictionary was published not in Russia but in India, and the most comprehensive, albeit having numerous inaccuracies and errors, list of Sanskrit-Russian correspondence was made not by a linguist but by a historian and ethnographer Natalia Guseva, could not be considered as normal.

Although the first draft contains about 500 entries and the total number of collected matches is about 1800, at this stage, the main achievement of the project is not the number of matches but the creation of a user-friendly working tool. The dictionary, initially started as a single Excel sheet, has been transferred into a specially designed electronic database with an interface for entering various data. Importantly, the database is able to compile a LaTeX code for producing a ready-to-print high resolution PDF version of the dictionary.

In the final part of the report a special attention was drawn to the importance of this work in addressing some issues relating to the ethnogenesis of the Slavs raised by O. N. Trubačёv: the time and place of formation of Proto-Slavonic dialects, relations between the Slavonic and Baltic languages, the problem of Iranian influence and the possibility of Slavonic-Indo-Aryan contacts.

The full video of the presentation can be accessed here.

The article in which I try to give an alternative etymology of the name of the Eastern-Slavonic god Xors (Hors) has finally been published in Studia Mythologica Slavica.

It is the result of several years of research and I consider it an important event in my academic work.

You can read it at my Academia.edu page

The paper examines the traditional explanation of the Eastern-Slavonic deity Xors as an Iranian loan from the Persian xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘sun’ and advances an alternative etymology via the Indo-Aryan root hṛṣ-, Indo-European *ghers/*g’hers and its cognates in other Indo-European languages. Based on the linguistic and mythological comparative analysis Xors is interpreted not as an abstract ‘solar god’ but as a ‘sun fertility hero’ viewed as the development of the ancient archetype of the ‘dying and resurrecting god’ comparable in role to Dionysus. The paper closes with a brief outline of some new venues for research following out of the proposed re-interpretation of Xors.

The traditional explanation of Xors as a late Iranian loan from the Persian xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘(radiant) sun’, conceived in the era when the Historical Linguistics was in its infancy, has now become an anachronism. It is not viable linguistically and is also a methodological dead-end because declaring Xors as an abstract generic ‘solar god’ or the ‘god of the solar disc’ does not really explain anything. Slavonic mythology and pre-Christian religious cults directly continue the Indo-European and Proto-Indo-European traditions so we should view the character and nature of Slavonic deities not as detached ‘exotic’ entities or endless ‘borrowings’ from surrounding peoples but as local developments of the common ancient base-myths. The new etymology of Xors as a relic of the I-E *h(V)rs-, preserved to this day in toponyms in the Balkan and Circumpontic areas and in numerous cognates in the principal I-E language branches, integrates Xors-Daž’bog into the mainstream of the pan-European and Eurasian mythology. It also helps to understand the intricate deep connection of the multitude of seemingly diverse Eurasian cults and myths which may all decent to the same fundamental Palaeolithic archetypes of the ‘Great Mother’, ‘Divine Marriage’ and the eternal ‘wheel’ of birth and dying repeated at all levels from plants, animals, humans to the seasonal and cosmic cycles.

Russian summary

Неиранское происхождение восточнославянского бога Хърса/Хорса.

Константин Л. Борисов

Несмотря на то, что в древнерусских исторических и религиозных источниках Хорс является вторым по частоте упоминаний после верховного языческого бога Перуна, о его роли в пантеоне древних славян практически ничего не известно. В этой статье делается попытка нового осмысления функции Хорса через метод сравнительного лингвистического и мифологического анализа.

В самых ранних исторических исследованиях Хорс описывался как славянский аналог греческого Бахуса (Дионисия), а также сравнивался с древнепрусским божеством плодородия Curcho. Однако, с середины девятнадцатого века прочно утвердилась теория об иранском происхождении имени Хорс, как прямого заимствования из персидского xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘солнце-царь’. На этом основании Хорс представляется как ‘солнечный бог’ или как некое абстрактное ‘божество солнечного диска’. Такая интерпретация Хорса и сегодня является общепризнанной среди историков. При этом игнорируются объективные сложности произведения имени ‘Хорс’ из иранского xoršid. Такая радикальная трансформация звучания не характерна для известных иранских заимствований в славянский. В частности, необъясним предполагаемый переход иранского š в s. Кроме того, слово xwaršēδ появилось в средне-иранском языке относительно поздно (не ранее IV в. до н. э), как сокращённый вариант Авестийского hvarə хšаētəm ‘солнце сияющее, правящее’, и не является собственно теонимом. С последующим развитием Зороастризма функции солярного бога Hvar перешли к переосмысленному Митре (Mihr), и само его имя стало уже использоваться как синоним солнца. В современных иранских языках xoršid также имеет значение ‘солнце’, но без какого-либо религиозного подтекста.

Наряду с лингвистическими есть и культурно-исторические препятствия иранского происхождения теонима ‘Хорс’. Несмотря на то, что образ солнца занимает важное место в славянском фольклоре, зачастую солнце представлялось как ‘девица’. Однако главной проблемой в теории об иранском происхождении Хорса является вопрос о том, когда и при каких условиях славяне вообще могли заимствовать солнечный культ и название солнечного бога у иранцев.

Изначальная проблематичность теории прямого заимствования из иранского заставляла многих исследователей искать альтернативные объяснения. В частности, были попытки использования фонетической близости восточнославянского ‘хорошо/хорош’. При этом, как правило, не подвергался сомнению постулат о солярной сущности Хорса и его иранском происхождении. Основная трудность на этом пути состоит в том, что отсутствует надёжная этимология самого слова ‘хорошо/хорош’ и его конкретный иранский источник. Возможность прямого родства с практически полностью фоно-семантически совпадающим древне-индийским hṛṣu ‘радостный, довольный’ не рассматривается a priori, ввиду якобы невозможности прямого контакта древних славян с индо-арийскими языками в силу их географической удалённости и установившимся предубеждением, что любые схождения сакральной и религиозной лексики славянского с индо-иранским следует рассматривать исключительно как заимствования из иранских языков посредством скифского.

Данная работа опирается на возможность сохранения в Северном Причерноморье этноса или языковых реликтов прото-индо-иранского языка, восходящего ко времени Ямной культуры (3600—2300 до н. э.), до его предполагаемого разделения на индо-иранскую и иранскую ветви. Отталкиваясь от кардинального значение корня hṛṣ в древне-индийском, как ‘ощетинивание, эрекция’, возводимому к праиндоевропейскому этимону *ghers(*g‘hers-) ‘ощетиниваться’, теоним ‘Хорс’ интерпретируется как божество плодородия, сочетающее функции ‘солнечного героя’ и ‘хтонического бога’, сравнимого по функции с греческим Дионисом и его аналогами в других европейских и восточных культах.

В заключительной части коротко описываются некоторые перспективы сравнительного мифологического анализа, которые открываются благодаря новой интерпретации образа Хорса как отражения древнего ‘дионисийского комплекcа’.

I made a modest contribution to making the program about Swastika: Reclaiming the Swastika on BBC Radio 4 (to be broadcast at 11:00 on Friday 24 October – and on the BBC iPlayer for 30 days after broadcast). It has been prepared by Mukti Jain Campion. I would like to recommend it to all my followers. Please also read the feature story by Mukti Jain Campion on BBC Magazine How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it.