You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘etymology’ tag.

Browsing the Internet, I came across multiple threads discussing “Vedic Astronomy,” claiming that “Rig Veda describes Sun Orbit and attraction of planets.” Several stanzas of Rig Veda (10.22.14, 10.149.1, 1.164.13, 1.35.9) are usually quoted to support this claim. I would like to demonstrate that the “translation” of the Rig Veda hymn 1.35.9 which is repeated and re-posted across various sites and blogs:

“The sun moves in its own orbit but holding earth and other heavenly bodies in a manner that they do not collide with each other through force of attraction.”

is false and misleading.

I have just finished studying this hymn and can recite most of it by heart so I was stunned by this “translation” which has nothing to do with the original Vedic text. If you have the desire, patience and a bit of spare time I intend to demonstrate why it is a falsification and a hoax.

The stanza 1.35.9 is important because it is an essential part of the upanayana ceremony (for Vaishya). The exact text of this stanza (with accents) is as follows:

हिर॑ण्यपाणिः सवि॒ता विच॑र्षणिरु॒भे द्यावा॑पृथि॒वी अ॒न्तरी॑यते

अपामी॑वां॒ बाध॑ते॒ वेति॒ सूर्य॑म॒भि कृ॒ष्णेन॒ रज॑सा॒ द्यामृ॑णोति

in the IAST transliteration:

híraṇyapāṇiḥ savitā́ vícarṣaṇir ubhé dyā́vāpr̥thivī́ antár īyate

ápā́mīvām bā́dhate véti sū́ryam abhí kr̥ṣṇéna rájasā dyā́m r̥ṇoti

Padapatha (with joining sandhi [H1] and accents removed) transliteration is:

hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ǀ savitā ǀ vi-carṣaṇiḥ ǀ ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ ǀ īyate ǀ

apa ǀ amīvām ǀ bādhate ǀ veti ǀ sūryam ǀ abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām ǀ ṛṇoti ǁ

Now we come to the most important part of translating these two lines. Some of Indian readers may exclaim at this point “Never read translations of Vedas by Western scholars! They make mistakes because in Sanskrit a single word has multiple meaning” so I invite you to join the quest and follow the translation procedure step by step.

First of all, we need to separate the two processes “translation” and “interpretation”.

The translator’s goal is to faithfully capture the essence of the original text, ensuring that the translated version maintains the same grammatical structure and literal meaning as the source. It involves a meticulous process of understanding the grammar, syntax, and nuances of both the source language and the target language. In our case this task can be quite challenging because we are dealing with ancient texts like the Rig Veda, which was originally composed in a language known as “Vedic,” separated from our times by at least 3500 years.

Interpretation involves the analysis and explanation of the meaning behind the text. While translation focuses on conveying the literal meaning, interpretation aims to uncover the underlying messages, symbolism, and cultural significance within a given piece of work.

Now to our translation of 1.35.9.

Since Russian in many ways preserves the ancient Indo-European and Vedic grammar (having similar declension and conjugation patterns), we shall analyse the text using the method of questioning used in teaching Russian grammar at school.

The first important step is to determine the Actor or the Subject of the sentence. It is not always easy in some stanzas but, fortunately, in our case it is straightforward. We ask the question WHO? The obvious answer is savitā. By its ending –ā we deduce that this is Nominative case, singular, masculine from the nominal base savitṛ-. The base ending tṛ- tells us that it is an agent noun or ‘performer/doer’ . Taking this ending off we get the base savi– and further taking off the linking vowel we arrive to the bare root sau-/sav-. By applying backwards the vṛddhi phonetic rule we come to the elementary verbal root sū-. It is one of the most fundamental Vedic roots meaning ‘to set in motion, urge, impel, vivify, create, produce’. This root makes such important words as sūrya ‘the Sun’, sūnu m. ‘a son, child, offspring’ and many others.

Putting it all together as savitṛ- we confidently establish the meaning as ‘one who sets in motion, urges, impels, vivifies, creates, produces’. This agrees well with the character of the Sun or a solar deity.

The next question is WHAT savitā? There are two adjectives coordinated with savitā in Nominative case, singular, masculine (case ending –ḥ) describing his qualities: hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ and vi-carṣaṇiḥ.

The first one is a compound with the first component hiraṇya– ‘gold; golden, made of gold’ and the second is pāṇi– ‘hand’ (originally *palni related to Gk. παλάμη; Lat. palma; Angl.Sax. folm). The compound is thus confidently translated as ‘golden-handed’.

The next word vi-carṣaṇiḥ is somewhat more challenging. Taking off the case ending we get the base ví-carṣaṇi-, removing the prefix vi- we obtain the adjective carṣaṇi– deriving from the verbal root kṛṣ- with the central meaning ‘to drag, pull; make furrows, plough’ (the initial c is a palatalised k). Following the ancient Indian grammarian Yāska this word is to be translated as ‘ploughing, cultivating’ meaning more broadly ‘busy doing something, active’. Notably, this word sounds in tune with the verb vi-car- with the cardinal meaning ‘move swiftly, rove , ramble about or through, traverse’ giving an additional feeling of swift motion. The allusion to ploughing and being busy may give a clue why this stanza was specifically chosen for Vaishya in upanayana ceremony. Furthermore, in Vedic there is a plural noun carṣaṇi ‘cultivators (opposed to nomads)’, men, people, race’ meaning the five peoples (páñca carṣaṇī́ḥ ‘five peoples’ in RV 5.86.2). There is yet another possible explanation. Rig Veda has been passed orally for many generations before it was written down. Although the priests did their best to transfer it on as precisely as possible we cannot exclude chances of mispronunciation or mistake. There is a verb cakṣ– ‘to see, to observe’ and its prefixed form vicakṣ– ‘to see distinctly, view’. Perhaps we should read this problematic word as vi-cakṣaṇiḥ meaning ‘seeing, observing’. This agrees with the character of Savitṛ- as ‘overseeing all living creatures’.

We can now translate the Actor/Subject hiraṇya-pāṇiḥ ǀ savitā ǀ vi-carṣaṇiḥ as ‘golden-handed, busily acting Savitr’ also keeping in mind the intricate (and probably intentional) association of vi-carṣaṇiḥ with swiftness and also with ‘cultivators (opposed to nomads)’, men, people, race’.

Next comes the question WHAT DOES HE DO? To answer it we need to look for all verbs in the stanza. We easily identify four verbs īyate, bā́dhate, véti and ṛṇoti. They all have Present Tense, 3 person, singular (he/she/it) endings -te/-ti so we are sure that they all relate to savitā. Let us go though them one by one.

(1) īyate is the intensive form of the verb i- ‘to go quickly or repeatedly, to come, wander, run, spread, get about ‘. This matches the character of Savitr/Sun.

(2) bādhate is a form of the root bādh– with the Vedic meaning ‘to press, force, drive away, repel, remove’.

(3) veti is a form of the root vī– ‘to set in motion, arouse, excite, impel; to go, approach’.

(4) ṛṇoti is a form of the root ṛ- ‘to go, move, rise, tend upwards; to go towards, meet with, fall upon or into, reach, obtain’.

Combining the answers to the questions WHO? and DOING WHAT? we form the back-bone structure of our translation:

golden-handed, busily acting (or overseeing?) Savitr (1) goes quickly, traverses (somewhere), (2) drives away/repels (something), (3) sets in motion, arouses, impels (something), (4) rises, goes (upon or towards something or somewhere).

We only need to fill in the missing bits by asking secondary questions.

- GOES WHERE? ubhe ǀ dyāvāpṛthivī ǀ antaḥ where ubhe is an Accusative dual form of ubha both (compare Russian oba, obe ‘both’); dyāvāpṛthivī is a “dvanda” compound made of words dyāvā ‘heaven’ + pṛthivī ‘the earth or wide world’ also Accusative dual; final word antaḥ/antar means ‘between’. The answer is ‘going/traversing between both heaven and earth’.

- REPELLS WHAT? apa ǀ amīvām where apa is ‘away, off’ and amīvām is an Accusative plural form of amīva- ‘distress, terror, fright; tormenting spirit, demon; affliction, disease’. The answer is ‘drives away/repels distresses/diseases’.

- SETS IN MOTION, AROUSES WHAT? sūryam Accusative of sūrya ‘Surya/Sun’. The answer is ‘sets in motion/arouses Surya/Sun’.

- REACHES WHAT? or RISES/ GOES WHERE? abhi ǀ kṛṣṇena ǀ rajasā ǀ dyām where abhi is ‘into, over, upon; to, towards, in the direction of, against, by’; kṛṣṇena is the Instrumental (here expressing Locative) of kṛṣṇa ‘dark, black’, rajasā is Instrumental (expressing Locative) of rajas ‘region (the intermediate sphere of vapour or mist, region of clouds)’ and the Accusative dyām of div, dyu ‘heaven, the sky’. The words kṛṣṇena rajasā are treated grammatically as a pair but they form a single entity meaning ‘dark + (intermediate) region’ so we translate it as a singular. The answer is ‘into/over/upon the dark (intermediate) region of the sky’.

Now we can assemble all the elements and get the whole translation (still in need of polishing):

Golden-handed, busily acting (or overseeing?) Savitr goes/traverses quickly/repeatedly between both heaven and earth, (he) wards off/repels distresses/diseases, (he) incites/arouses Surya/Sun, (he) reaches/rises/goes towards the sky/heaven over/upon/towards the dark-intermediate-region.

Lets us now compare our raw translation with that of Sri Aurobindo

The golden-handed all-seeing Savitri is moved between both Heaven and Earth ; {he} drives away grief, carries the Sun , goes by the dark Mid-world to Heaven .

As you can see both texts are similar in sense. The one by Sri Aurobindo is more concise but the key-words have references to the dictionary providing additional details which reflect his vision and interpretative of the Vedas. The obvious difference, however, is the translation of the obscure word vi-carṣaṇiḥ. According to Mayrhofer “The existence of an adjective carṣaṇiḥ “mobile, active, active” [….] is entirely doubtful” he only accepts the meaning ‘people, race. tribe’. There is a very similarly sounding adjective vicakṣaṇa ‘conspicuous, visible, bright, radiant, splendid; clear-sighted (lit. and fig.), sagacious, clever, wise’ from the verb vi-cakṣ ‘to see distinctly, view, look at, perceive, regard’. Its present tense, 3 person sing. form is vi-caṣṭe ‘(he) sees distinctly, views, looks at’ so, apparently, in the Sri Aurobindo’s translation this word was understood in this sense because Savitr in other stanza is described as overseeing all creatures (RV 1.35.2 “ā́ devó yāti bhúvanāni páśyan” ‘drives god Savitr overseeing living creatures’). There is no way we can translate this word exactly and it has to be interpreted in some way. So, for example, in the Russian translation by Elizarenkova this passage is interpreted as “Golden-armed Savitar, ruler of the human race.” In Geldner’s German translation this word is translated as “der Ausgezeichnete” ‘magnificent, beautiful’.

Here we come to the crucial point of interpretation. One can interpret this stanza meaning in many ways. If you practice the traditional Hinduism, you will interpret Savitr as one of the deities of the Vedic pantheon, and one of the Adityas, i.e., offspring of the Vedic deity Aditi. If you share the ideas of Dayanand Saraswati you will view Savitr as another word for “sun” and as one of the manifestations of The Supreme Lord. In either case, your understanding/interpretation may be different, but this does not mean that you may freely alter the grammar, syntax, and other fundamental elements of the literal translation. Therefore, the cosmic “translation” from which we started our discussion is totally false and misleading.

I hope that you enjoyed the voyage to the awesome world of Rig Veda. Please feel free to comment or ask questions.

[H1]fusion of sounds across word boundaries and the change of sounds due to neighbouring sounds or due to the grammatical function of adjacent words.

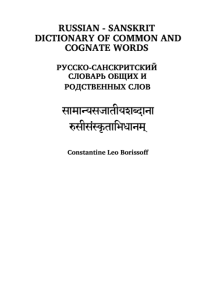

I have not published any new posts for several years but the work on the comparative dictionary was continuing. Regrettably, my co-author and teacher Alexander Shaposhikov died last year. However, he has finished most of his part of work and also left many comments that allow me to continue with this project and lead it to the end. Currently, the dictionary is 90 per cent complete. It contains approximately 870 completed entries out of a total of 1000 planned. I hope to publish the dictionary by September 2023.

The dictionary is the first comprehensive study of lexical similarities between Russian and Sanskrit. In creating it, the authors drew on the contributions and historical works of Russian and other linguistic researchers of etymology, especially the Russian Academician O. N. Trubachev and “Etymological Dictionary of Slavic Languages” published by Vinogradov Instutute of Russian Language. This is a demonstration draft with only a small number (90) of entries including words starting with (russian) B (rating 5-3). Progress since the previous draft:

The introductory part has been thoroughly edited and page typesetting largely completed (hyphenation, “hanging” prepositions, spacing etc.).

Dictionary entries have been edited, style and spelling corrected. Proper typesetting of dictionary entries is still to be done. Biblio references were checked, sorted and standardised to GOST. Cover draft was slightly edited.

Please note that in the online text the Devanagari ligatures are not always reproduced correctly and some words seem stuck together, so we recommend to download a .pdf file which is fairly small in size.

________________________

Cловарь является первым систематическим сводом лексических схождений русского и санскрита. При его создании авторы опирались на достижения исторического языкознания, работы по этимологии российских и зарубежных исследователей и особенно на наследие академика О. Н. Трубачёва и «Этимологический словарь славянских языков. Это демонстрационный черновик с небольшим количеством (90) слов, начинающихся с (рус.) B (рейтинг 5-3).

Прогресс по сравнению с предыдущим черновиком:

Вступительная часть тщательно отредактирована, в основном завершена верстка страниц (расстановка переносов, «висячие» предлоги, интервалы и т. д.).

Словарные статьи отредактированы, исправлены стиль и орфография. Надлежащая верстка словарных статей еще предстоит. Библиографические ссылки были проверены, отсортированы и приведены в соответствие с ГОСТ. Проект обложки был немного отредактирован.

Обратите внимание, что в онлайн-тексте лигатуры деванагари не всегда воспроизводятся правильно, а некоторые слова кажутся слипшимися, поэтому мы рекомендуем вам скачать файл .pdf, который имеет довольно небольшой размер.

Мы приветствуем любую конструктивную критику и комментарии.

The article in which I try to give an alternative etymology of the name of the Eastern-Slavonic god Xors (Hors) has finally been published in Studia Mythologica Slavica.

It is the result of several years of research and I consider it an important event in my academic work.

You can read it at my Academia.edu page

The paper examines the traditional explanation of the Eastern-Slavonic deity Xors as an Iranian loan from the Persian xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘sun’ and advances an alternative etymology via the Indo-Aryan root hṛṣ-, Indo-European *ghers/*g’hers and its cognates in other Indo-European languages. Based on the linguistic and mythological comparative analysis Xors is interpreted not as an abstract ‘solar god’ but as a ‘sun fertility hero’ viewed as the development of the ancient archetype of the ‘dying and resurrecting god’ comparable in role to Dionysus. The paper closes with a brief outline of some new venues for research following out of the proposed re-interpretation of Xors.

The traditional explanation of Xors as a late Iranian loan from the Persian xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘(radiant) sun’, conceived in the era when the Historical Linguistics was in its infancy, has now become an anachronism. It is not viable linguistically and is also a methodological dead-end because declaring Xors as an abstract generic ‘solar god’ or the ‘god of the solar disc’ does not really explain anything. Slavonic mythology and pre-Christian religious cults directly continue the Indo-European and Proto-Indo-European traditions so we should view the character and nature of Slavonic deities not as detached ‘exotic’ entities or endless ‘borrowings’ from surrounding peoples but as local developments of the common ancient base-myths. The new etymology of Xors as a relic of the I-E *h(V)rs-, preserved to this day in toponyms in the Balkan and Circumpontic areas and in numerous cognates in the principal I-E language branches, integrates Xors-Daž’bog into the mainstream of the pan-European and Eurasian mythology. It also helps to understand the intricate deep connection of the multitude of seemingly diverse Eurasian cults and myths which may all decent to the same fundamental Palaeolithic archetypes of the ‘Great Mother’, ‘Divine Marriage’ and the eternal ‘wheel’ of birth and dying repeated at all levels from plants, animals, humans to the seasonal and cosmic cycles.

Russian summary

Неиранское происхождение восточнославянского бога Хърса/Хорса.

Константин Л. Борисов

Несмотря на то, что в древнерусских исторических и религиозных источниках Хорс является вторым по частоте упоминаний после верховного языческого бога Перуна, о его роли в пантеоне древних славян практически ничего не известно. В этой статье делается попытка нового осмысления функции Хорса через метод сравнительного лингвистического и мифологического анализа.

В самых ранних исторических исследованиях Хорс описывался как славянский аналог греческого Бахуса (Дионисия), а также сравнивался с древнепрусским божеством плодородия Curcho. Однако, с середины девятнадцатого века прочно утвердилась теория об иранском происхождении имени Хорс, как прямого заимствования из персидского xwaršēδ/xoršid ‘солнце-царь’. На этом основании Хорс представляется как ‘солнечный бог’ или как некое абстрактное ‘божество солнечного диска’. Такая интерпретация Хорса и сегодня является общепризнанной среди историков. При этом игнорируются объективные сложности произведения имени ‘Хорс’ из иранского xoršid. Такая радикальная трансформация звучания не характерна для известных иранских заимствований в славянский. В частности, необъясним предполагаемый переход иранского š в s. Кроме того, слово xwaršēδ появилось в средне-иранском языке относительно поздно (не ранее IV в. до н. э), как сокращённый вариант Авестийского hvarə хšаētəm ‘солнце сияющее, правящее’, и не является собственно теонимом. С последующим развитием Зороастризма функции солярного бога Hvar перешли к переосмысленному Митре (Mihr), и само его имя стало уже использоваться как синоним солнца. В современных иранских языках xoršid также имеет значение ‘солнце’, но без какого-либо религиозного подтекста.

Наряду с лингвистическими есть и культурно-исторические препятствия иранского происхождения теонима ‘Хорс’. Несмотря на то, что образ солнца занимает важное место в славянском фольклоре, зачастую солнце представлялось как ‘девица’. Однако главной проблемой в теории об иранском происхождении Хорса является вопрос о том, когда и при каких условиях славяне вообще могли заимствовать солнечный культ и название солнечного бога у иранцев.

Изначальная проблематичность теории прямого заимствования из иранского заставляла многих исследователей искать альтернативные объяснения. В частности, были попытки использования фонетической близости восточнославянского ‘хорошо/хорош’. При этом, как правило, не подвергался сомнению постулат о солярной сущности Хорса и его иранском происхождении. Основная трудность на этом пути состоит в том, что отсутствует надёжная этимология самого слова ‘хорошо/хорош’ и его конкретный иранский источник. Возможность прямого родства с практически полностью фоно-семантически совпадающим древне-индийским hṛṣu ‘радостный, довольный’ не рассматривается a priori, ввиду якобы невозможности прямого контакта древних славян с индо-арийскими языками в силу их географической удалённости и установившимся предубеждением, что любые схождения сакральной и религиозной лексики славянского с индо-иранским следует рассматривать исключительно как заимствования из иранских языков посредством скифского.

Данная работа опирается на возможность сохранения в Северном Причерноморье этноса или языковых реликтов прото-индо-иранского языка, восходящего ко времени Ямной культуры (3600—2300 до н. э.), до его предполагаемого разделения на индо-иранскую и иранскую ветви. Отталкиваясь от кардинального значение корня hṛṣ в древне-индийском, как ‘ощетинивание, эрекция’, возводимому к праиндоевропейскому этимону *ghers(*g‘hers-) ‘ощетиниваться’, теоним ‘Хорс’ интерпретируется как божество плодородия, сочетающее функции ‘солнечного героя’ и ‘хтонического бога’, сравнимого по функции с греческим Дионисом и его аналогами в других европейских и восточных культах.

В заключительной части коротко описываются некоторые перспективы сравнительного мифологического анализа, которые открываются благодаря новой интерпретации образа Хорса как отражения древнего ‘дионисийского комплекcа’.

I have decided to upload a draft of my RUSSIAN – SANSKRIT DICTIONARY OF COMMON AND COGNATE WORDS which is the result of some eight years of work. This dictionary has been conceived as a practical reference book with the objective of providing factual material for researchers in the field of the Indo-European linguistics or anyone interested in etymology, semantics and the origin of the Indo-European, particularly, Slavonic languages. Compiling a dictionary is time-consuming and it is a mammoth task to do for a single person. The first draft published here is only a rough approximation. It contains only 488 entries, which is about a quarter of the planned volume, and still lacks some essential parts in the Introduction section. The entries have not yet been properly proof-read and I am constantly updating the comments.

You may access the text at my page on Academia.edu

Although this work is titled ‘Dictionary’ it is neither a traditional Russian-Sanskrit dictionary nor a formal etymological dictionary, but rather a catalogue of various cognate, common or otherwise connected Russian and Sanskrit words, arranged is a systematic way with cross-references, explanatory notes, links to other Slavonic and Indo-European languages, indexes and other features aimed at making it a valuable and convenient reference book. The specific task called for employing both Cyrillic and Devanagarī scripts throughout the book because transliteration, however elaborate, cannot fully replace the native writing system. Since it is unlikely that every reader would be proficient in both scripts, each word is accompanied by a conventional transliteration.

In writing this book I endeavoured to go through all major works dedicated to this issue starting from the discovery of Sanskrit and its relation to the European languages in general, and particularly to Slavonic, covering the period from the 17th century up to the modern days. Each proposed cognate word has been carefully evaluated, checked through various dictionaries and, sometimes, re-linked or rejected. This method provided some eight hundred pairs that made the back-bone of the dictionary. The rest of the cognate pairs (about another thousand two hundred) are the result of many years of scrupulous research.

Many cognate pairs are obvious, some need more or less detailed explanations and might be difficult to apprehend without some basic knowledge of the principal linguistic concepts and terms. This is why the dictionary is prefaced by an Introduction containing some essential information about the Russian and Sanskrit languages and their phonetic and grammatical features with particular attention to the principal rules of sound correlation. This section is now in work and it is not included in this draft.

I would be grateful for any constructive criticism or comments. If you would like to support this project there are several ways of helping me with the work:

- report any spelling or other mistakes that you have noticed

- suggest any other cognate pairs

- check the various cognates I mention in Slavonic and other languages if they happen to be in your native language

I would like to demonstrate here the remarkable phonetic affinity between Sanskrit and Russian taking two dozen of unquestionable cognate pairs as examples. It is well known that all Indo-European languages contain a greater or lesser number of common words but only Slavonic and, to a lesser degree, Baltic languages approximate Sanskrit to such an extent that in me instances the difference between certain Slavonic languages could be greater than between some Slavonic languages and Sanskrit.

Take the word for `spindle’: Sanskrit vartana, Russian vereteno, Bulgarian. vretе́no, Slovenian vreténo, Czech vřeteno, Polish wrzeciono, Upper Sorbian wrjećeno and Lower Sorbian rjeśeno. The phonetic shape of cognates in other Indo-European languages differs considerably.

A good example is the word `alive’: Sanskrit jīva, Russian živ, Lithuanian gývas, Greek bíos, Latin vīvus, Irish biu, Gothic qius, Old High German quес, and English quick.

Transliteration notes

Sanskrit: ā, ī, ū – long sounds; ṛ = ri (a short i similar to Rus. soft рь/r‘); c=ch; j similar to j in “jam”; ṣ similar to sh; ś a subtler sort of sh, closer to German /ch/ as in ich.

Russian: š similar to sh; č = ch; ž = like g in garage , the vowel y is a sort of ‘hard’ i sounding somewhat similar to unstressed i in Eng. it . the sign ‘ indicates softness and stands for a very short i . Vowels with j are iotated so ju would be similar to Eng. you and Skr. yu etc.

| Skt. | Rus. | Lith. | Greek | Latin | Goth. | OHG/Ger. | Eng |

| bhrātṛ | brat | brólis | phrátēr | frāter | brōþar | Bruder | brother |

| bhrū | brov’ | bruvis | ophrus | brāwa | brow | ||

| vidhava | vdova | vidua | widuwō | Widuwō | widow | ||

| vartana | veretenò | Wirtel | spindle | ||||

| viś | ves’ | viešė | oikos | vīcus | weihs | abode, village, home | |

| vātṛ | veter | vėtra | wind | ||||

| vṛka | volk | vilkas | lýkos | lupus | wulfs | Wulfs | wolf |

| dvār | dver’ | dùrys | thýra | forēs | daúr | turi | door |

| dvaya | dvoe | dvejì | twaddjē | two of smb. | |||

| devṛ | dever’ | dieveris | daḗr | lēvir | zeihhur | husband’s brother | |

| dina | den’ | dienà | diēs | day | |||

| dam, dama | dom | nãmas(?) | dō̂ma | domus | house, home | ||

| janī | žena | gynḗ | qino | wife | |||

| jīva | živ | gývas | bíos | vīvus | qius | quес | alive |

| jñāna | znanie | žinios | gnōsis | knowledge | |||

| kada | kogda | kada | when | ||||

| katara | kotoryj | kuris | póteros | uter | ƕаþаr | hwedar | which |

| kumbha | kub | kýmbos | cupa | pitcher | |||

| laghu | ljogok | leñgvas | elaphrós | levis | leihts | lungar | light |

| roci | luč | leukós | lūх | liuhaþ | light, ray | ||

| madhu | mjod | medùs | méthy | metu | honey | ||

| mūṣ | myš’ | mŷs | mūs | mûs | mouse | ||

| mās | mjaso | mėsà | mimz(?) | meat |

Note that we compare the attested languages and not hypothetical `reconstructions’ however, according to Antoine Meillet:

“[..] Baltic and Slavic show the common trait of never having undergone in the course of their development any sudden systemic upheaval. […] there is no indication of a serious dislocation of any part of the linguistic system at any time. The sound structure has in general remained intact to the present. […] Baltic and Slavic are consequently the only languages in which certain modern word-forms resemble those reconstructed for Common Indo-European.” ( The Indo-European Dialects [Eng. translation of Les dialectes indo-européens (1908)], University of Alabama Press, 1967, pp. 59-60).

See also my other posts:

https://borissoff.wordpress.com/2012/11/18/russian-sanskrit-verbs-3/

https://borissoff.wordpress.com/2012/12/13/russian-sanskrit-nouns/

It is well known that in Iranian languages airiia- / airya- had a clear ethnic meaning which is reflected in the modern name of the country Iran.

However, in Sanskrit, this word had a more general meaning: ‘a good worthy family man who respects the traditions of his country, who is a good housekeeper and duly performs the rites of yajña’:

This is how ārya is translated in the MW dictionary:

(H1) ā́rya [p= 152,2] [L=26533] m. (fr. aryá , √ṛ) , a respectable or honourable or faithful man , an inhabitant of āryāvarta

[L=26534] one who is faithful to the religion of his country

[L=26535] N. of the race which immigrated from Central Asia into āryāvarta (opposed to an-ārya , dasyu , dāsa)

[L=26536] in later times N. of the first three castes (opposed to śūdra) RV. AV. VS. MBh. Ya1jn5. Pan5cat. &c

[L=26537] a man highly esteemed , a respectable , honourable man Pan5cat. S3ak. &c

[L=26538] a master , an owner L.

[L=26539] a friend L.

[L=26540] a vaiśya L.

[L=26541] Buddha

[L=26542] (with Buddhists [pāli ayyo , or ariyo]) a man who has thought on the four chief truths of Buddhism (» next col.) and lives accordingly , a Buddhist priest

[L=26543] a son of manu sāvarṇa Hariv.

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26544] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. Aryan , favourable to the Aryan people RV. &c

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26545] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. behaving like an Aryan , worthy of one , honourable , respectable , noble R. Mn. S3ak. &c

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26546] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. of a good family

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26547] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. excellent

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26548] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. wise

(H1B) ā́rya [L=26549] mf(ā and ā́rī)n. suitable

(H1B) ā́ryā [L=26550] f. a name of pārvatī Hariv.

(H1B) ā́ryā [L=26551] f. a kind of metre of two lines (each line consisting of seven and a half feet ; each foot containing four instants , except the sixth of the second line , which contains only one , and is therefore a single short syllable ; hence there are thirty instants in the first line and twenty-seven in the second) ; ([cf. Old Germ. êra ; Mod. Germ. Ehre ; Irish Erin.])

One conclusion which can be drawn from the above is that the widespread translation of ārya only as ‘noble’ or ‘distinguished’ (e.g. in Encyclopædia Britannica) is clearly a simplification. Also the meaning ‘of the race which immigrated from Central Asia into āryāvarta (opposed to an-ārya , dasyu , dāsa)’ may originate in the specific interpretation of Rig Veda by the 19th century European (mostly German) scholars. The key to understanding the primordial meaning of ārya could be in the cardinal meaning of the root but there is a problem with its identification.

The ār may be considered as a separate root but it may also be a vṛddhi of the verb ṛ having lots of meanings : ‘to go, move, rise, tend upwards; to advance towards a foe, attack, invade; to put in or upon, place, insert, fix into or upon, fasten; to deliver up, surrender, offer, reach over, present, give’ etc. Such conflicting meanings is an indication that there could be several separate verbs merged in this root.

Such a wide range of meanings is a source of conflicting explanations of arya / ārya. Somehow it is often overlooked that there is an obscure verb ār – *āryati ‘to praise’ which may be connected to ṛ. This verb has been poorly attested only tree times in RV as 3 P, pl. āryanti (RV 8.016.06 & RV 10.048.03 (twice)) but there is also a prominent noun arka ‘praise, hymn, song; one who praises, a singer’ which may be related here. The final -ka is a diminutive/comparative suffix (much used in forming adjectives; it may also be added to nouns to express diminution, deterioration, or similarity e.g. putraka, a little son; aśvaka, a bad horse or like a horse) having clear parallels in Slavonic ( e.g. Rus. znat‘ ‘to know’ > znajka ‘one who knows’ etc.). Interestingly, in Rus. dialects there is a verb arkat’ ‘to cry, speak loudly’. From this perspective ārya could have originally meant simply ‘the praised one = good respectable person’ being synonymous to śravya ‘worth hearing, praiseworthy’ (cp. also śravaḥ ‘glory, fame, loud praise’ and its Rus cognate slava ‘fame, glory’).

This is how this word is explained in our Russian-Sanskrit Comparative Dictionary:

“Vedic ā́rya-, āryaḥ has no commonly accepted etymology. Formally, it appears to be a derivative from some verbal stem ār- with a suff. -ya-. The most plausible correlation could be with the Ved. verb ār-, ā́ryanti ‘to praise’ and its Passive Future Participle ārya (f. āryā) ‘to be praised, revered’. This is supported by the exact morphological match and synonym vándya ‘to be praised, praiseworthy’ deriving from the Ved. verb vand-, vándate ‘to praise, celebrate, laud, extol; to show honour, do homage, salute respectfully or deferentially, venerate, worship, adore’. Furthermore, it is generally compatible with the Skt. (epic) adj. śrāvya- (śravya-) ‘audible, to be heard, worth hearing’ from the verb śru-, śrūyáte (passive.) ‘to be celebrated or renowned’ (Passive Future Participle śravya (f. śravyā)). All these words are united by the common meaning “praised, renowned, worthy of respect””

In Rig Veda ārya is met about 30 times. I looked at two RV verses which are often cited in the literature on this topic and tried to translate them as close as possible to the text.

(RV text from Rigveda )

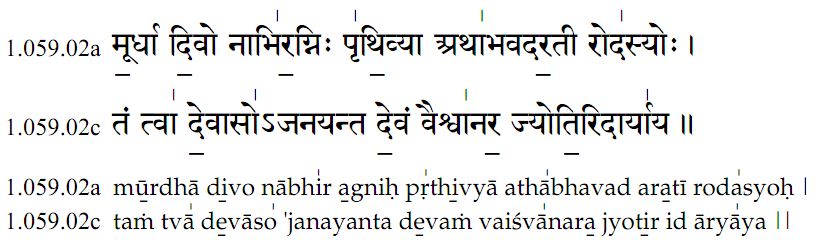

1.059.02

mūrdhā divo nābhir agniḥ pṛthivyā athābhavad aratī rodasyoḥ |

taṃ tvā devāso janayanta devaṃ vaiśvānara jyotir id āryāya||

Agni (is) the head of the Sky, the navel of the Earth. He became the messenger of the two worlds |

Such you were born by Gods. О, Vaishvanara! Indeed you are the (celestial) light for the Arya ||

7.005.06

tve asuryaṃ vasavo nyṛṇvan kratuṃ hi te mitramaho juṣanta |

tvaṃ dasyūṃr okaso agna āja uru jyotir janayann āryāya||

Into you the Vasus have put the power of an Asura for they appreciate the strength of your spirit, O, (you) great as Mithra |

You chased away the Dasyu from (his) abode creating the broad light for the Arya ||

Some general observations. Both verses are addressed to Agni and in both of them is mentioned the celestial light jyotiḥ.

This word, which could be the key to understanding the verses, has the following meanings (in Vedic)

1) light (of the sun , dawn , fire , lightning , &c. ; also pl.), brightness (of the sky)

2) light appearing in the 3 worlds , viz. on earth , in the intermediate region , and in the sky or heaven

3) eye-light

4) the light of heaven , celestial world

5) light as the type of freedom or bliss or victory

In post-Vedic times it acquired an even more philosophical meaning: ‘human intelligence’ and ‘highest light or truth’.

The two verses, although they appear in different books of Rig Veda, are coined by the same template and could be variations of the same invocation:

Agni is addressed with all fitting praises and epithets and thanked for giving the ‘light’:

in 1.059.02 : vaiśvānara [relating or belonging to all men, omnipresent, known or worshipped, everywhere, universal, general, common] jyotir [light] id [indeed] āryāya [for the Arya (Gen. case)].

in 7.005.06: uru [wide, broad, spacious, extended, great, large, much, excessive, excellent] jyotir [light see above.] janayann [creating] āryāya [for the Arya (Gen. case)].

As it is usually the case with ancient texts, these verses are subject to interpretations depending on what sense you put into jyotiḥ and ārya . Note that in the second verse there are mentioned dasyu [enemy of the gods, impious man, any outcast or Hindu who has become so by neglect of the essential rites]. However, it is important that both Dasyu and Arya are mentioned in singular. Therefore, one can interpret them as ethnonyms but, in my view, keeping in mind that the cardinal meaning of ārya in Vedic was ‘a good, faithful person’, this could be also interpreted as ‘an impious man’ vs. ‘a faithful man’. In modern terms it may be defined as ‘fidel’ vs. ‘infidel’. I am particularly inclined to understand it in this way because Agni is not thanked for giving the land or cities of ‘Dasyu’ but for the ‘light’ in the broadest philosophical sense and agree with Kuiper (Aryans in the Rigveda. Amsterdam; Atlanta: Rodopi, 1991, pp. 90–93) that the creators of Rig-Veda considered as `aryas’ anybody who followed the Vedic traditions and performed the sacred yajña rites.

According to post-Vedic native lexicographers ārya adj. means : coming from a good family; venerable (pūjya), excellent (śreṣṭha), understanding (buddha) (Amarakośaḥ, Śabdaratnāvalī).

I would like to conclude this short essay by quoting Hans Hock:

“Close examination of the textual evidence regarding the “white” vs. “black” distinction turns out strongly to suggest that it refers, not to a distinction in skin, but to an “ideological” one between “bad” and “good”

(Hock, H. H., Bauer, B. & Pinault, G.-J. (Eds.), Did Indo-European linguistics prepare the ground for Nazism? Lessons from the past for the present and future. Language in time and space: A festschrift for Werner Winter on the occasion of his 80th birthday, de Gruyter, 2003, 167-187).

Reccomended further reading on this subject: No Racism in Rig Veda by by Kant Singh

This is a list of some most obvious Russian – Sanskrit cognate nouns. It is only a short-list in which I give only the generally accepted cognate pairs having the rating 5 & 6. Since one should compare similar forms, I give Russian nouns in a special transcription, approximated to Sanskrit Latin transliteration. Read the rest of this entry »

The topic of Iranian loans into Slavonic has become a common place in Slavistics reflecting, to a considerable extent, the stereotype view on Slavonic mainly as a target language for borrowing. In reality, the number of truly attested Iranian loans is confined to a rather short list of words. Strictly speaking, the term ‘iranism (иранизм)’, widely used in Russian linguistic literature, stands for a direct borrowing from one of the attested Iranian languages. However, according to the academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Oleg Nikolajevič Trubačev, such loans are limited to a few cultural terms such as *kotъ ‘stall, small cattle shed’, *čьrtogъ ‘inner part of a house’, *gun’a ‘shabby clothes, rags’, *kordъ ‘short sward’, *toporъ ‘axe’ etc., plus a separately standing group of religious terms and names of gods. However, even if any of these words are indeed borrowings they may not necessarily be ‘iranisms’ in the true sense (i. e. direct borrowings from one of the attested Iranian languages). Read the rest of this entry »

This is a short list of some most obvious Russian – Sanskrit cognate verbs. Since one should compare similar forms, I give Russian verbs in the same format as Sanskrit verbs are presented in traditional dictionaries (for example in Monier Williams’ Sanskrit-English Dictionary): verbal root – 3rd person, singular, Present Tense form. For a comparison of conjugation paradigms see my other post. See also the Russian – Sanskrit nouns

I had a pleasure of meeting Bakhtiyar Amanzhol at the Musical Geographies of Central Asia conference.  His presentation Musical Instruments of Tengrianism was very informative and interesting but I could not quite agree with the etymology of “Tengri”:

His presentation Musical Instruments of Tengrianism was very informative and interesting but I could not quite agree with the etymology of “Tengri”:

“The historical roots of Tengrianism extend deep into history. The earliest references to Tengri date back to the 4th century B.C.: in ancient Mesopotamia the name of a king would be written with an honorific title, “Dingir” (God). It has been argued that by the twelve-thirteenth century A.D. this form of worship had become a religion in its own right, with its own ontology, cosmology, mythology and demonology. Variants of the word tengri, usually meaning “god”, are found in a wide range of Turkic languages, and there have been many speculations about its etymology. The Russian researcher of Tengrianism, Rafael Bezertinov, conveys a sense of its meaning for Altaic worship by collating the Turkic word “таң” which means “sunrise”, with the ancient Egyptian word “rа” which means “sun”, and the Turkic, Altaic word “yang”, meaning “consciousness”. “

I find the etymology, proposed by Rafael Bezertinov particularly doubtful. Read the rest of this entry »